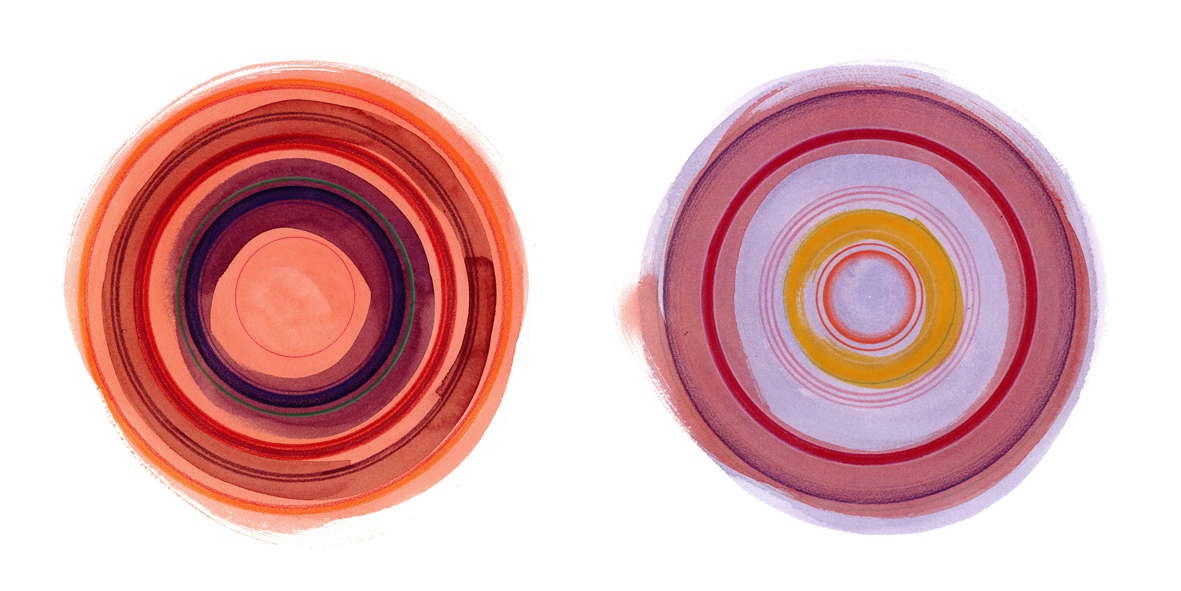

My final blog post undoubtedly needs to include the images created from all this wine research and testing. Of the six red wines tested and included in this body of work, two are represented below – one wine was made in Canberra, the other in South Australia.

My previous posts have elaborated on why these artworks have been created, and their use in the scientific method at the AWRI. Now that my highly collaborative residency comes to a close I ask myself how these images might be further developed through the creative process.

Looking at art and drinking wine at the same time is a familiar experience to me, the art world pairs the two in an almost obligatory manner. Yet for the regular consumer, wine is served and consumed at home, probably while sitting at a table. So I am suspicious of turning these artworks into purely wall-based images, when it seems there is a perfectly good alternative surface in the mix – the table top. Beyond this notion my ideas are too unrefined to try and lay out here. Over the next 12 months I hope to develop the images into new forms which speak of not only the scientific context in which they were made, but the site of hospitality in which they could be used.